Californians could drink highly purified sewage water that is piped directly into drinking water supplies for the first time under proposed rules unveiled by state water officials.

The drought-prone state has turned to recycled water for more than 60 years to bolster its scarce supplies, but the current regulations require it to first make a pit stop in a reservoir or an aquifer before it can flow to taps.

The new rules, mandated by state law, would require extensive treatment and monitoring before wastewater can be piped to taps or mingled with raw water upstream of a drinking water treatment plant.

“Toilet-to-tap” this is not.

Between flush and faucet, a slew of steps are designed to remove chemicals and pathogens that remain in sewage after it has already undergone traditional primary, secondary and sometimes tertiary treatment.

It is bubbled with ozone, chewed by bacteria, filtered through activated carbon, pushed at high pressures through reverse osmosis membranes multiple times, cleansed with an oxidizer like hydrogen peroxide and beamed with high-intensity UV light. Valuable minerals, such as calcium, that were filtered out are restored. And then, finally, the wastewater is subjected to the regular treatment that all drinking water currently undergoes.

“Quite honestly, it’ll be the cleanest drinking water around,” said Darrin Polhemus, deputy director of the state’s Division of Drinking Water.

The 62 pages of proposed rules, more than a decade in the making, are not triggering much, if any, debate among health or water experts. A panel of engineering and water quality scientists deemed an earlier version of the regulations protective of public health, although they raised concerns that the treatment process would be energy-intensive.

“I would have no hesitation drinking this water my whole life,” said Daniel McCurry, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Southern California.

This water is expected to be more expensive than imported water, but also provide a more renewable and reliable supply for California as climate change continues. Most treated sewage — about 400 million gallons a day in Los Angeles County alone — is released into rivers, streams and the deep ocean.

The draft rules, released on July 21st, still face a gauntlet of public comment, a hearing and peer review by another panel of experts before being finalized. The State Water Resources Control Board is required by law to vote on them by the end of December, though they can extend the deadline if necessary. They would likely go into effect next April and it will take many years to reach people’s taps.

Heather Collins, water treatment manager for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, said the regulations will give the district more certainty about how to design a massive, multi-billion dollar water recycling project with the Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts. The district imports water that is provided to 19 million Southern Californians.

The joint effort, called Pure Water Southern California, has already received $80 million from the state. The first phase of the project, which could be completed by 2032, is expected to produce about 115 million gallons of recycled water a day, enough for 385,000 Southern California households.

Most is planned to go towards recharging local water agencies’ groundwater stores, but about 20% could be added to drinking water supplies upstream of Metropolitan’s existing treatment plant for imported water.

“We’re excited,” Collins said. “It helps better inform us on what our project needs to include, so that we can have a climate-resistant supply for our agencies in Southern California.”

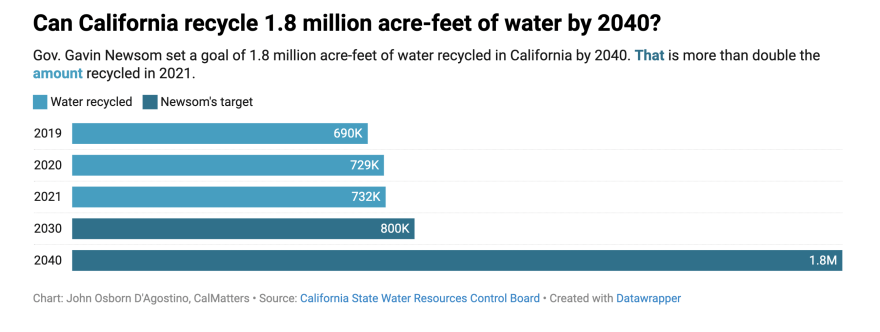

The new rules come as endless cycles of drought leave California’s water suppliers scrabbling for new sources of water, like purified sewage. In 2021, Californians used about 732,000 acre feet of recycled water, equivalent to the amount used by roughly 2.6 million households, though much of it goes to non-drinking purposes, like irrigating landscapes, golf courses and crops.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom called for increasing recycled water use in California roughly 9% by 2030 and more than doubling it by 2040.

“Water recycling is about finding new water, not just accepting the scarcity mindset — being more resourceful in terms of our approach,” Newsom said last May in front of Metropolitan’s Pure Water Southern California demonstration plant.

Some recycled water is already used to refill underground stores that provide drinking water, a process called indirect potable reuse, employed beginning in the 1960s in Los Angeles and Orange counties. But a water agency must have a clean and convenient place to store the expensive, highly-purified water. “You don’t want to inject this recycled wastewater that you’ve spent all this effort cleaning into a dirty, polluted aquifer just to ruin it again,” McCurry said.

To expand these uses, state lawmakers in 2010 tasked the water board with investigating the possibility of adding recycled water either directly into a public water system or just upstream of a water treatment plant. In 2017, they set a deadline to develop the regulations by the end of 2023.

California won’t be the first; Colorado already has regulations and the nation’s first direct potable reuse plant was built in Texas in 2013. Florida and Arizona have rules in the works.

California’s statewide rules, however, are expected to be the most stringent, said Andrew Salveson, water reuse chief technologist at Carollo Engineers, an environmental engineering consulting firm that specializes in water treatment.

“They are more conservative than anywhere else,” he said. “And I’m not being critical. In the state of California, because we’re in the early days of (direct potable reuse) implementation, they’re taking measured and conservative steps.”

Removing viruses and chemicals

The water that flushes down toilets, whirls down sinks, runs from industrial facilities and flows off agricultural fields is teeming with viruses, parasites and other pathogens that can make people sick. Chemicals also contaminate this sewage, everything from industrial perfluorinated “forever chemicals” to drugs excreted in urine. Bypassing groundwater stores or reservoirs to funnel purified sewage directly into pipes means that there’s less room for error.

The new regulations would ramp up restrictions on pathogens, calling for scrubbing away more than 99.9999% of diarrhea-causing viruses and certain parasites. Also a series of treatments are designed to break down chemical contaminants like anti-seizure drugs, pain relievers, antidepressants and other pharmaceuticals. Medications can bypass traditional sewage treatment so they are found in low concentrations in recycled sewage and groundwater.

The added technologies are good at washing away pharmaceuticals, McCurry said, so having them “back-to-back introduces a ton of redundancy,” he said. “Any pharmaceutical you could think of, if you tried to measure it in the product water of one of these plants, is going to be below the detection limit.”

The new rules call for extensive monitoring to ensure the treatment is working. Some harmful chemicals, such as lead and nitrates, which are dangerous to babies and young children, will be tested for weekly; others, monthly. And water providers must also monitor the sewage itself before it even reaches treatment for any chemical spikes that could indicate illegal dumping or spills.

“We think we’ve got the chemical classes covered in the treatment processes, so that we’re removing materials that we don’t even know are there,” the water board’s Polhemus said.

Jennifer West, managing director of WateReuse California, a trade association for water recycling, said she was happy to finally see California’s regulations, though she hopes the state will build in more flexibility for water providers to alter the suite of treatments as technologies change.

Richard Gersberg, San Diego State University professor emeritus of environmental health, said he supports using highly treated waste for drinking water. But he suggests that the state fund long-term studies comparing health effects in people who drink it to those whose drinking water comes from another source, such as rivers, “which might end up being worse. Probably is,” he said.

Given the vast and changing cocktail of chemicals constantly in use, “we don’t know what we don’t know,” Gersberg said. “If this becomes huge in California, and it will, I believe … we should at least spend a little money.”

Who will be first?

All this treatment and monitoring is likely to be pricey, which is why Polhemus expects to see it largely limited to large urban areas that produce a lot of wastewater, such as Los Angeles County. The Metropolitan Water District’s $3.4 billion estimate for building the project dates back to 2018, and has likely increased since then, according to spokesperson Rebecca Kimitch.

For small and medium communities, Polhemus said, "it doesn’t pencil in a small scale type of arrangement.”

The Orange County Water District, which has long been a leader in purifying recycled water, has concluded that piping it directly to customers doesn’t pencil out for them, either, because they’ve already invested so heavily in refilling their carefully tended aquifer.

It would “require adding more treatment processes and increasing operating expenses,” board president Cathy Green said in a statement. “Local water agencies are currently well-equipped to continue to supply drinking water to customers in our service area at a low cost using the Orange County Groundwater Basin.”

For other regions like Silicon Valley, though, the costs may be worth it as climate change continues to shrink state supplies.

“At this point, it’s more expensive than water we might import during a drought. But who knows what will happen in the future,” said Kirsten Struve, assistant officer in the water supply division at the Santa Clara Valley Water District, which serves approximately 2 million people.

“That’s why we need to get prepared.”

The Santa Clara water agency, known as Valley Water, is planning a $1.2 billion project in Palo Alto to produce about 10 million gallons a day of water for groundwater recharge, but Struve said she hopes the plant also will be used for direct potable reuse in the future.

The timing of the regulations has butted up against the realities of planning for Monterey One Water on the Monterey Peninsula as well. The utility has been injecting purified wastewater into the seaside aquifer for three years, producing about a third of the local supply, said General Manager Paul Sciuto. It is working on expanding the project by 2025, Sciuto said.

“I get that question of, ‘This water is so pure, why do you put it in the ground? Why can't you just serve it?’ " he said. “And I always fall back on, well, there's no regulations that allow us to do that at this point.”

Now that the state is closer to finalizing them, he said, “there's a point on the horizon to shoot for.”

CalMatters is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.