Editor’s Note: This is the first story in a two-part collaboration between Oregon Public Broadcasting and KUNC, Community Radio for Northern Colorado.

Northeastern Oregon’s rocky mountains and arid, shrub-steppe valleys might seem like unforgiving terrain for most creatures. But wolves thrive here.

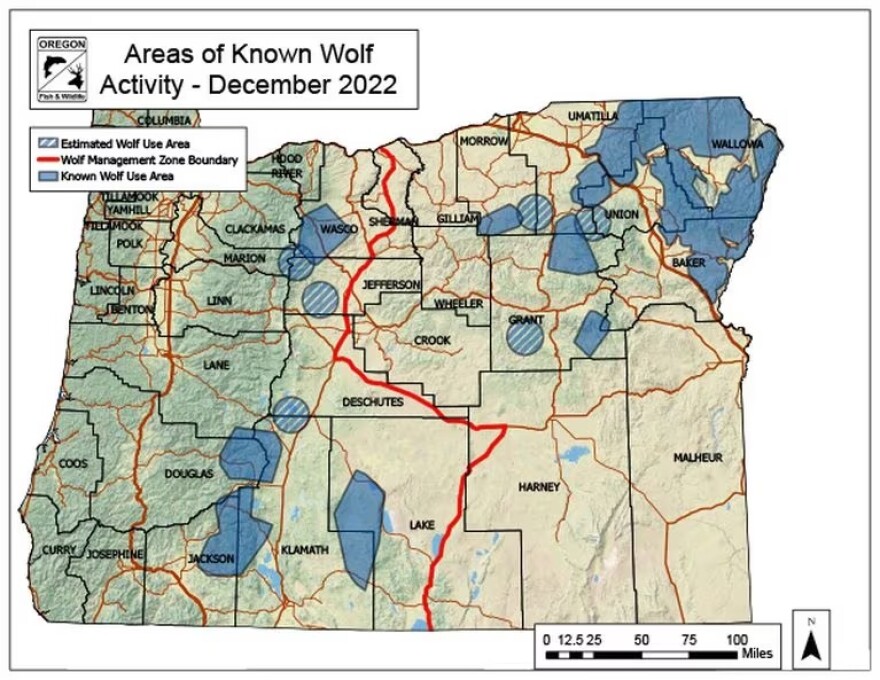

Most of Oregon’s 38 known wolf packs roam this region, where the relative isolation compared to the state’s western half gives them more freedom to travel, and to hunt. They prey on mule deer and elk, and when those are tough to come by, rabbits and grouse. Sometimes that’s not enough, especially for growing pups, so they turn to cattle pastures.

As Oregon’s wolf population has grown over the last two decades, from 14 to at least 178, so have their encounters with livestock. Ranchers, in turn, have become tired of wiring their pastures with electrical fencing, of sleeping in their trucks in fields, of finding dead guard dogs and shredded calves. Beyond tired, many ranchers are angry and want wolves gone.

Yet they don’t want the animals sent to Colorado.

On Sunday, wildlife experts flew helicopters through northeastern Oregon and caught five wolves (see video below), then released them in Colorado the next day. The plan is to relocate up to 10 wolves over time in hopes of restoring Colorado’s wolf population. On its face, the plan would seem to be cause for celebration among ranchers who want fewer wolves in Oregon, as well as environmental groups who support wolf restoration. But as with anything involving wolves, some Oregonians’ feelings about Colorado’s plan are complicated, with differing opinions divided between areas that rarely see this formidable animal, and the others that often do.

Starting East

Kelly Birkmaier likes to call out to the cows grazing in a small pasture by her house outside Enterprise, Oregon.

She yells, “Wooo-ooh!” Cows start mooing back one by one, until much of the herd is beckoning and trotting toward her, emerging from the morning mist.

She and her husband, Tom Birkmaier, raise these cows for beef. Although they run a business in which cows are the products, Kelly Birkmaier says it’s hard to rear animals from birth without forming a connection with them.

“They come to us when we call them,” she said. “They look for us for help.”

Tom Birkmaier keeps most of their 500-cattle herd in another pasture almost an hour away, where he spends most of his time keeping an eye on them.

“When we are being hit by the wolves, I’m hardly never here,” he said, “because I [am] sleeping in my pickup at night or sleeping out on the hillside, or walking through them all night long.”

Last year was his worst yet; he says he lost about 20 calves to wolf attacks. He recalls one spring morning when he found his cattle huddled in a corner of the pasture: “I tried to take the cows back up a canyon to get them to a better spot, and they just absolutely would not go. And I finally got them to start up this canyon, and then I started finding the calves that were tore up.”

When wolves attack, they don’t usually wait for their prey to die before they start eating. They just eat while the other animal fights to survive. The result can be gruesome.

It’s especially hard on mother cows when they have to watch their dead calves being hauled away.

“They would come and run by me and follow me and bawl, wondering… wanting me to give them their calf back,” Tom Birkmaier said.

Wolf attack deterrents do exist. There’s something called fladry — bright flags hung from an electric fence wire. Or anything that emits flashing lights and loud sounds. The state offers financial assistance for these tools, and it compensates ranchers for confirmed wolf attacks on livestock.

But for the Birkmaiers, the state’s compensation is not enough to make up for the long-term impacts of trauma on the herd, which can include weight loss and fewer pregnancies. Those, in turn, lead to financial losses.

Tom Birkmaier says wolf attacks also put emotional stress on his family, as he spends his days and nights in the pasture, protecting their cattle from attacks.

For all those reasons, the Birkmaiers say they’re against Colorado relocating 10 wolves from Oregon — with Colorado ranchers in mind.

“It’s just going to bring the problem over to a lot of ranchers and end up killing a lot of livestock in Colorado,” Tom Birkmaier said.

Lawmakers in other wolf states share a similar sentiment. Idaho, Wyoming and Montana have all refused Colorado’s request for wolves, despite their sizable populations. During their 2022 wolf counts, Wyoming had 338, Montana had 1,087 and Idaho had 1,337 — all significantly larger than Oregon’s 178.

Idaho and Wyoming officials said they opposed Colorado’s plan to reintroduce wolves to that state because they feared it would potentially impact ranchers in nearby states.

“Idaho has paid an enormous price to have wolves on the landscape,” Idaho Fish and Game Director Jim Fredericks wrote in a letter to Colorado officials in June, citing costs associated with wolves killing livestock and “loss to rural economies due to decreased elk populations and hunting activity.”

Heading West

Gray wolves once thrived through Oregon and across the West, but a 19th-century extermination campaign led by ranchers almost wiped them out by 1950. About a decade later, attitudes toward wolves started changing as more biologists understood the role wolves play in a healthy ecosystem.

“They help keep disease from spreading in elk and deer herds because they target the weak and sick members of the herd,” said Bethany Cotton, conservation director with the Eugene-based nonprofit Cascadia Wildlands. “And they help keep other animals on the move, which helps riparian habitat.”

By 1999, after not being seen in Oregon for nearly six decades, a lone gray wolf wandered onto Oregon soil from Idaho. More wolves naturally migrated here over time, settling and creating new packs. In 2009, Oregon officials counted 14 wolves. Their numbers quickly grew, and the state saw double-digit percentage increases ever since. But that growth has plateaued these last few years.

Oregon's Wolf Population

Oregon's wolf population grew quickly, but has stagnated in recent years. An increase in human-caused wolf mortalities could be partly to blame.

For that reason, many local conservation groups are also against sending Oregon’s wolves to Colorado.

“Oregon’s wolf population remains quite small and has unfortunately stopped growing in any significant way in the last several years,” Cotton said.

Officials with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife attribute the trend to a concentration of wolf packs in northeastern Oregon. They say competition for food and territory is causing wolf numbers to stabilize naturally.

Colorado plans to only take healthy, young wolves between ages 2 and 5, when wolves typically split to create new packs. Some conservationists are concerned that those are the wolves Oregon needs most to continue rebuilding its population — especially west of the Cascade mountains, where there are fewer packs.

“It does make me question how that would impact recovery both in the short term and potentially longer term,” said Danielle Moser, wildlife program manager with Oregon Wild.

The stagnation among Oregon’s wolves could be partly caused by a rise in human-caused deaths.

The number of Oregon wolves killed by humans increased from six to 17 by 2022. That includes state-sanctioned wolf kills. Oregon grants wolf kill permits to ranchers if a pack is suspected of repeatedly killing livestock. In a few cases, wildlife officials allowed hunters to kill wolf pups if they believed packs were killing livestock to feed their litters.

Wolf kill permits only apply to the eastern part of the state, where wolves aren’t federally protected under the Endangered Species Act.

In July, Oregon started issuing more, less restrictive wolf kill permits to ranchers. Oregon Fish and Wildlife officials say staff have become more efficient when it comes to issuing wolf kill permits. As a result, this has been Oregon’s deadliest year for state-sanctioned wolf kills; there were 16 by mid-December. The state never had more than nine state-sanctioned wolf kills in previous years, not since pioneers’ 19th century extermination campaign.

In contrast to Oregon-based conservationists, many national groups applaud Colorado’s plan to relocate wolves from Oregon, including Defenders of Wildlife, the National Wildlife Federation and the Center for Biological Diversity. Many advocated for the 2020 Colorado ballot measure supporting wolf recovery that 50.9% of voters approved.

Staff with those groups say they understand local concerns about Oregon’s wolf conservation taking a step back, but they still consider Colorado’s plan a win for wolf conservation as a whole.

“If the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has deemed that this translocation is not going to have a negative impact on the Oregon wolf population, I trust the wildlife agencies that know the local wildlife management needs best,” said Brian Kurzel, executive director of the National Wildlife Federation’s regional office in Colorado.

Now to Colorado

Colorado is covering the costs of trapping and relocating the wolves, including contracting helicopter pilots, conducting health assessments on trapped wolves, and securing them in crates before flying them southeast.

Oregon wildlife officials are helping Colorado find packs by tracking collared wolves, as well as getting permission from Oregon landowners to access properties.

Colorado is also paying to collar the wolves it traps, even the ones it ultimately doesn’t take.

“So now we benefit from not having to do that field work and get an additional collar out to help monitor our population,” said Derek Broman, the game program manager at Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Restoring animal populations by moving them between states isn’t new. In the early 1900s, Wyoming donated a couple dozen Rocky Mountain elk to Oregon.

“We’re continuing a long history of states helping each other meet their conservation goals,” said Michelle Dennehy, the department’s spokesperson.

But Wyoming’s contribution alone didn’t help restore Oregon’s elk population, according to state documents, which say their recovery was largely a result of regulations protecting the few that remained in the state at the time.

Similarly, biologists say 10 wolves likely isn’t enough to reestablish wolves in Colorado. So far, only Oregon has agreed to contribute. Even so, Colorado officials are optimistic that they’ll get more in future years.

“I’m not concerned that we only have 10 wolves from Oregon,” said Eric Odell, who oversees species conservation at Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “In fact, I’m quite pleased that we have that, and I think that we’re well on the way to achieving our goal.”

That goal includes transferring between 10 to 15 wolves from different packs every year for the next three to five years. With Idaho, Wyoming and Montana off the table, Colorado officials are hoping to one day get the go-ahead from Washington state or a few tribal nations, including the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho. But if Washington and the tribes also decline the request, it’s unclear where Colorado will get the wolves it needs.

Copyright 2023 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit Oregon Public Broadcasting.