Members of the fishing industry are planning a protest Tuesday night to voice their concerns over offshore wind development in Oregon, and to ensure they are involved in choosing the location of turbines.

Offshore wind energy production remains fairly untapped throughout the country. No offshore wind farms have been built off the West Coast. That could soon change with President Biden's goal of developing the equivalent of 30 gigawatts of offshore wind turbines by 2030.

Three of those gigawatts could be built off the Oregon coast, enough to power over two million homes. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, is the federal agency that leases ocean waters for oil drilling and renewable energy production.

BOEM recently began calling for commercial wind energy producers to show their interest in developing offshore wind in Oregon. The agency identified over 10,000 square miles of ocean it says are ideal for wind farms.

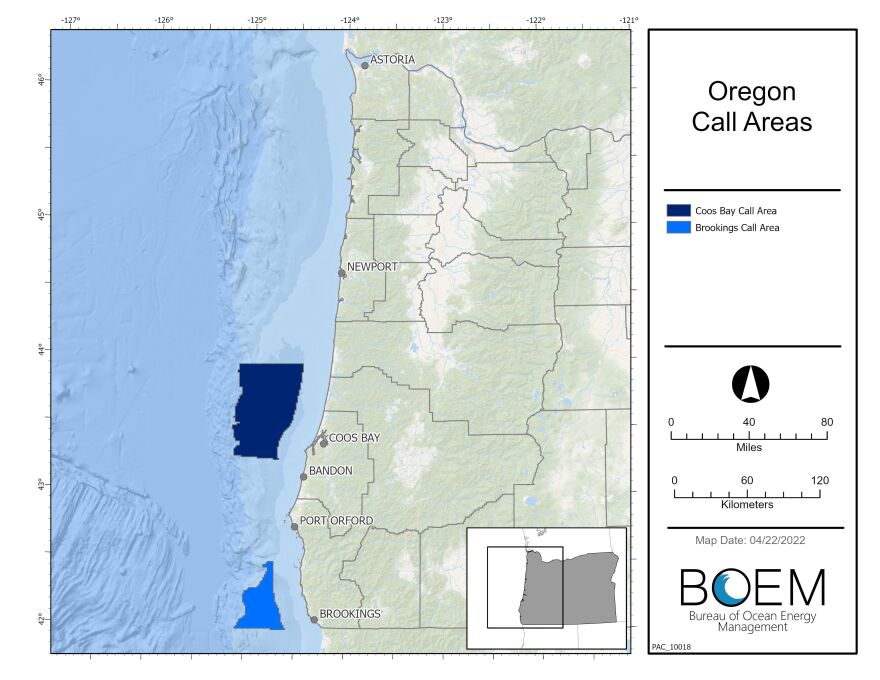

Those miles are split into two "call areas", one west of Brookings and the other off of Coos Bay.

While these wind farms could help the state meet its green energy goals, commercial fishermen have concerns about the effects these wind farms will have on fish stocks.

“We are talking about the ocean frontier,” says Mike Graybill, a marine biologist and the former manager of South Slough Reserve in Charleston. “And we are talking about, in Oregon, one of the most productive ocean areas on the planet, that already is a source of very, very important economic activity and is also an important source of our global food supply.”

Graybill says he’s been looking into what effects wind farms may have on the wildlife in the region. He says it’s important to look at these effects thoroughly because the West Coast is a prime location for fishing.

The West Coast lies in an eastern boundary current, where high winds blowing parallel to the coastline creates an upwelling current, forcing nutrient-dense water up to the surface.

Just five of these eastern boundary currents around the world produce almost a quarter of the world’s marine fish catch. The other four are off the coasts of Chile, Somalia, Northwest and Southern Africa.

“Everything from plankton to whales to seabirds to fish is associated with the fact that when wind blows over the oceans, it moves the water,” says Graybill.

That means offshore wind farms and fishing will likely clash, as both industries are connected, in some way, to wind.

“We’re very concerned that it’s going to lead to environmental and cumulative impacts that aren’t even being evaluated at this point,” says Lori Steele, director of the West Coast Seafood Processors Association. Steele helped to organize Tuesday's rally.

Steele says the fishing industry isn’t opposed to alternative energy. But, she says, the push for offshore wind energy isn’t being done responsibly and alternatives, such as onshore wind or solar farms, could be just as effective and cheaper than offshore wind.

While 10,000 square miles of ocean for wind farms seems like a lot, that entire area won’t be used for offshore wind. BOEM says the call areas are a broader identification where the agency is interested in leasing out to wind farm developers, and the actual size of the wind farms themselves will be smaller.

That call area will also be whittled down as the agency goes through the public comment period and identifies areas where wind farms may not be feasible, or where they would conflict too much with the fishing industry.

BOEM says coordination with the National Marine Fisheries Service, the Pacific Fishery Management Council and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife is already ongoing, and discussion will continue to help further reduce conflicts between wind power and fishermen.

According to Graybill, offshore wind turbines design makes fishing around them difficult and the locations must be picked carefully.

Graybill estimates up to 750 miles of cable could be needed to hold 200 wind turbines in place in deep water. The turbines float in the water and are each anchored by three cables attached to the seafloor.

“You won’t be able to tow a net that has 700 miles of mooring cables and 350 miles of electrical cables,” he says.

In Europe, where offshore wind has been in place since the '90s, fishermen frequently clash with energy companies to share the sea. They argue the exclusion zones around wind farms means more fishermen are competing for less space.

BOEM says it’ll continue to work with the fishing industry throughout this call process to avoid conflicts.

The agency is accepting public comments through June 28th. Members of the public can also look at interactive maps on BOEM’s website showing the specific call areas, and overlays of fish populations, existing underwater infrastructure and more.