When I was about 5 years old, my father passed away and life took a dramatic turn. My uncles from my father's side took all his properties, per the custom in my village in Ghana, so each of my father's seven wives had to find ways to provide and take care of their children. My mother struggled to get enough food — mainly beans and vegetables — to make even one daily meal for myself and my six siblings. She would make our food as spicy as possible so that we would have to drink a lot and fill our stomachs with water.

But during these difficult years when I was in primary school and junior high, my mother always made sure I went to school.

Primary and secondary school are not free in Ghana. At the beginning of each school term, my mother asked the headmaster if I could start classes while she tried to get money to pay the fees. I still remember one time, when I was 7 or 8, the school authorities got tired of her excuses and kicked me out of school.

The next day, Mom took her most precious clothing and traditional beads, which she had hidden in a trunk, and sold them for less than half their value. She used the money to pay my school fees. It was only about $10. It doesn't sound like much, but that was a lot of money in that time.

I was confused. Why hadn't she sold her belongings months ago to buy food for us? Her unselfish act made me regard education as a necessity.

My mother's sacrifice has been my anchor and source of strength ever since. My mom knew — and I later recognized — that education is more important than food. As a child, I realized that all the people in the village who could provide good food, school uniforms, books and shoes for their children had some form of education. I knew from that point that I could change my destiny if only I was able to succeed in school.

I completed high school, but it was nothing like high school in the United States. I never saw a computer. My school had no electricity; it had no library, gymnasium or cafeteria. I was picked on and beaten up by the other kids because I could not afford a school uniform.

In my senior year, my classmates and I had to take the final national exams that determine whether we could attend college. We knew even before starting the test that most of us would fail because our schools didn't have the staff and resources to teach us properly. Out of over 200 classmates, I was one of only seven who passed all seven subjects. But none of us earned scores high enough for admission to the public universities in Ghana. Still, to our classmates, we were heroes just for passing.

What would I do next?

During high school, I had served as a community health volunteer through the Ghana Health Service. I did receive money for my work, but that was not the only reward. As a volunteer, I carried vaccines to rural villages, sometimes walking for miles to deliver them. I felt satisfaction and joy as I administered the oral vaccines to infants and children, knowing that they would be protected from diseases that had killed many children.

But I wanted to be able to administer injectable vaccines. I wanted to help provide checkups and counseling for pregnant women. I wanted to be able to organize better preventive health services in these villages.

Even though I could not get into any university, I was able to qualify for a community health worker certificate program. It took two years to complete and was quite an intensive program.

I hoped that becoming a community health worker would help me achieve what I could not as a volunteer, but I soon realized that the care I could provide was not enough. I spent some time working with a medical team from Canada that visited remote villages, and I was amazed at the level of interaction with patients. They tried to explain a person's condition, whether drugs would help or not, and more. I vowed that if I ever got the opportunity to continue my medical education, it would be in Canada.

I asked a Peace Corps volunteer I had met to help me prepare a resume so I could apply for school. Little did I suspect that a year later, we would be married. After her two years of service, we moved to the United States derailing my Canada plans.

Education in America

We moved to Nevada. I got a job as a custodian in an elementary school and tried to enroll in a university, but the school wanted my high school transcripts. They were impossible to get. High schools in Ghana don't keep transcripts, just final exam results. I finally found one small community college that offered a placement test in lieu of high school transcripts.

This was a turning point. I felt I had another chance to change my destiny.

I was nervous as I started classes in January 2014. I considered myself to be the weakest academically among all the students. In the elementary school where I worked, I saw that all the students had laptops. How could I compete with these American students? I was fully discouraged. I felt that if any of these students studied for two hours, I would have to put in three times that effort to master the same material.

When I got my midterm exams and papers back, I first thought, "Oh, the professor has made a mistake; this cannot be my test score."

My scores were 95 percent, even 100 percent.

After my first semester, I transferred to a larger community college and continued to perform well. For the first time, I felt as if I was free from the limitations imposed on me by the environment and circumstances in which I grew up.

My next plan was to transfer to the local university to complete my undergraduate studies. But then I found out about a scholarship from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation for community college students transferring to a four-year university. This scholarship encouraged its applicants to apply to top schools in their field of interest. For me, that was public health — and Johns Hopkins University.

I didn't believe I had a chance in a million of being accepted into such a school, so I applied to another school known for its public health program: the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. I was accepted by both schools but did not get the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation scholarship. So Hopkins and North Carolina were out. I would instead go to the local university where I would get in-state tuition and a partial scholarship. My plan was to continue working as a custodian to help pay the bills.

But there was an unexpected twist. About a week after I was admitted to Hopkins and the University of North Carolina, both schools offered me a full scholarship. The door of opportunity opened again.

Still, I was afraid. I feared leaving behind my first American friends, my first American home, to go to a new place where nobody knew me.

I began school on Aug. 15, 2015. Last month, I graduated from Johns Hopkins University with a Bachelor of Arts in public health studies.

May 24, 2017, was the end of a long journey yet the beginning of a new chapter full of promises, difficult questions and deliberations. As I heard my name and began to walk across the stage, I wondered: How is this possible? In Ghana, I was not qualified to attend even a two-year college, yet here I am walking across the stage, graduating with honors, shaking the hand of the president of Johns Hopkins University.

I briefly thought: Maybe this is one of those good dreams that I will soon wake up from.

In America, I have learned, dreams can turn into an unexpected reality.

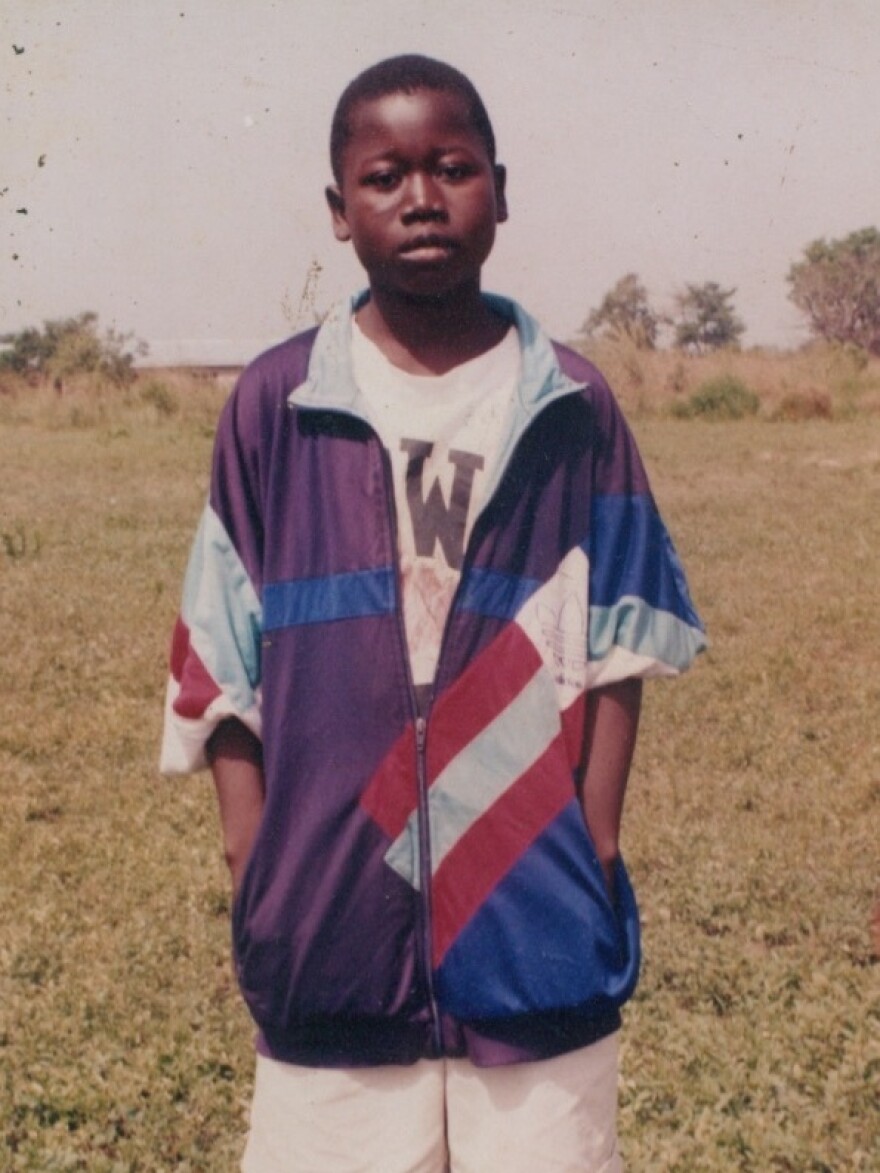

George Mwinnyaa, now 29, lives in Baltimore with his wife and 2-year-old son. He plans to start a master's program at the Bloomberg School of Public Health this fall.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.