The year 1903 may be best known as the year that the elephant Topsy was filmed while being electrocuted on Coney Island, or as the year that Ford Motor Company sold its first Model A to a dentist in Chicago. It was also the year Wilbur and Orville Wright, two brothers famous for their bickering, successfully flew the first powered airplane the world had ever seen.

Nineteen-o-three was also a big year in food history: it was then that a young German named Richard Hellman arrived in New York City where he would go on to open his own deli and create his famous recipe for mayonnaise; an enterprising Italian immigrant named Italo Marchiony received U.S. patent approval for his clever invention of edible ice cream cones; and Pennsylvania-born Milton Hershey broke ground for a chocolate factory in Derry Township.

Something else happened in food history in 1903 that is arguably as important as any of these noteworthy historical events. On May 5th, 1903, a 42-year-old English immigrant named Mary Elizabeth gave birth at her home in Hawthorne Park on Salmon Street in Portland, Oregon to a roly-poly baby. Rumor has it that the little giant weighed between thirteen and fourteen pounds. That baby, James Andrew Beard, would grow up to become one of the best-known and best-loved food connoisseurs in America.

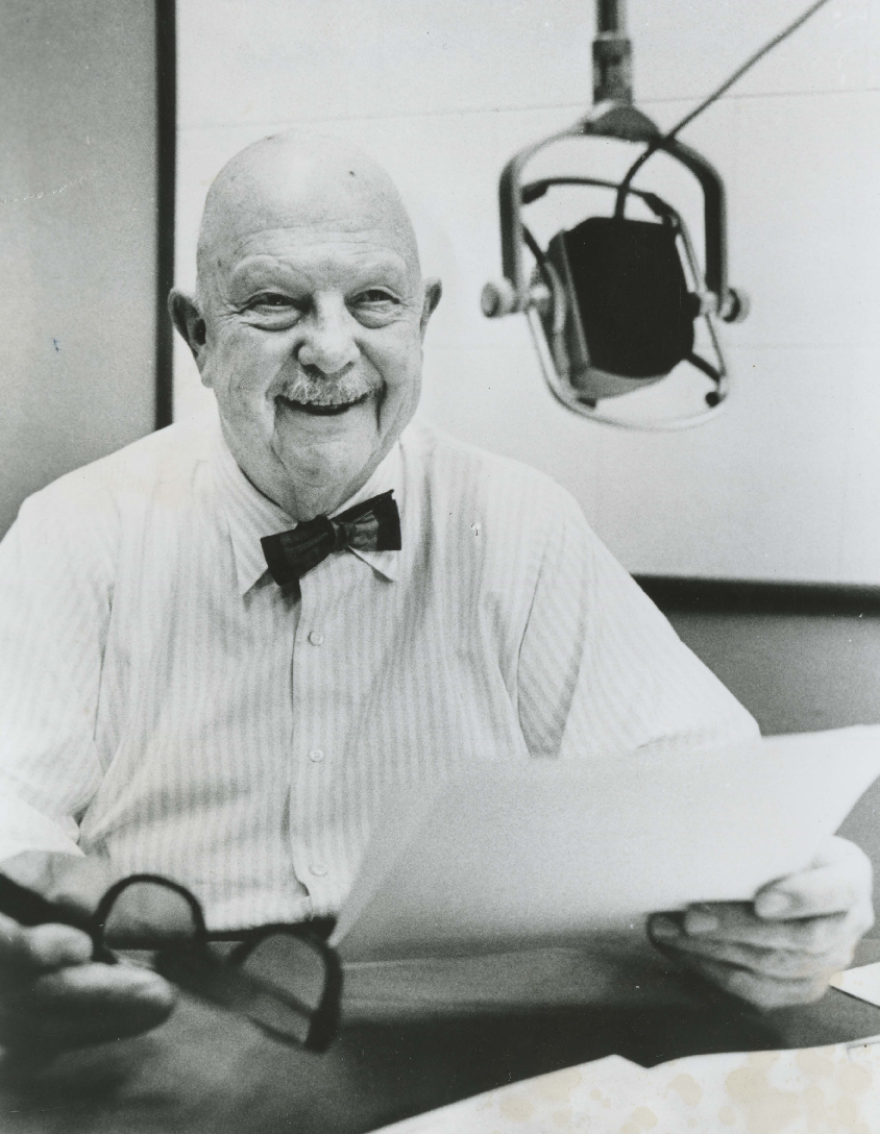

Even if you can’t immediately place the name, you’ve heard it before. Or maybe you recognize his photograph: the impossibly high forehead, bald pate, towering height, dapper bowtie, intelligent eyes, and sardonic yet always delighted and often sensual smile. Indeed, some thirty-five years after his death people—especially foodies—still love to talk about Beard. His brownstone in Greenwich Village has become the headquarters for the thriving James Beard Foundation, a non-profit that hosts master chefs, gives culinary scholarships to aspiring cooks, and carries on James Beard’s tradition of promoting a love of food. There are plans underway to open an open-air market in Portland, Oregon named after James Beard.

In high school I owned a beat-up mass market paperback of his best-selling Beard on Bread, a book which sold more copies than any of his others. The oatmeal bread came out as hard as a brick. As did the basic white bread. Back then, even though I only knew how to make scrambled eggs and ramen noodles, I blamed it on Beard. Years later, after I acquired a standing mixer with a dough hook, I would realize my bread failed because I was always too impatient to knead the dough properly.

So who was James Beard anyway? Irreverent, portly, enthusiastic, and known for being genial, flamboyant, and always opinionated, James Andrew Beard was the author of over 20 cookbooks. He made a name and a living for himself as a food columnist, TV show host, home chef, restaurant critic, and foodie extraordinaire. His attention was so coveted—a Beard stamp of approval during his lifetime was like a clothing endorsement from Michelle Obama during her husband’s presidency—that it’s been said that he never once paid for his own dinner out. Perhaps the best way to describe James Beard is with the phrase he used in one of his essays: he was a “food sensualist.”

James Andrew Beard was also a homegrown Oregonian, claiming that much of his taste and delight in food originated with his roots—in Portland—where his mother owned and ran a gentlefolk’s boarding house, as well as in Gearhart—on the Oregon Coast—where he spent part of every summer at a beach cabin, running around by the ocean’s edge, clamming, crabbing, eating home-cured ham the family brought from Portland, and reveling in the bounty of fresh foods local to the Pacific Northwest.

A Boyhood in Portland

While his birth would prove a boon to America’s food culture, James Beard’s parents did not have a happy marriage. By most accounts, John Beard and Mary Elizabeth Jones were a mismatched couple. Mary Elizabeth was a big-boned, ruddy, determined woman.

After Beard was expelled from Reed, he left Portland for London for voice training lessons.

One of twelve children born in southern England, she aspired to a middle-class life, loved the arts and music, and appreciated both good food and hard work. She left Victorian England on a boat bound for North America when she was seventeen years old. Always industrious and eager to travel and rub shoulders with interesting people, over time Mary became a cosmopolitan, highly cultured, and financially successful (though by no means rich) businesswoman. Beard’s biographers credit her with being one of the first American women in the burgeoning hotel business.

Jimmie’s father also came from a big family. Born in Iowa, John Beard was one of sixteen children. As Beard tells it, his father came to Oregon in a covered wagon when he was only five years old. Though he was the only Beard sibling to attend college—he studied to be a druggist—John was not worldly or interested in the arts or culture. An intelligent, dapper, quiet young man, he first married when he was twenty-three years old and sired two children. He met Mary Elizabeth, who also had a brief marriage to another man, after his younger daughter died of diphtheria in 1891 and his wife passed away from tuberculosis. Often low on money and a spendthrift, smaller in stature than Mary, and more interested in frequenting the seedier part of town than in family time, John, a single father to his older daughter Lucille, seemed an unlikely choice of husbands for the ambitious and independent Mary Elizabeth. But Mary Elizabeth wanted a child of her own and perhaps John was looking for a stepmother for Lucille. In any case, the two married in April 1898. They lived in the same house, but kept their finances separate and seem to have led very different, disconnected lives.

Mary Elizabeth liked to cook and loved to eat. A foodie before the term existed, she was an expert at bargaining for candied kumquats, chestnuts, and mandarin oranges in Chinatown; she harvested Gravenstein apples, Bing cherries, English walnuts, and large, juicy plums from the trees around her house; she grew fresh vegetables and herbs in the garden; and made her own sausages, cured hams, tea blends, and preserves. Little Jimmie grew fat and healthy on a rich diet of local foods: sweet cream from Mrs. Harris’s cow, puréed parsnips from the home garden, his mother’s canned asparagus salad, sautéed wild mushrooms harvested in town (which gives you an idea of how lush and verdant the city of Portland was at that time), Dungeness crab from the Oregon Coast, fresh Olympia oysters, and noodles expertly prepared in what Beard described as “a soup that was a rather weak chicken stock absolutely full of noodles, ham, scallions, and thin strips of egg…” by Jue-Let, the Chinese chef who worked for his mother and often cooked for James.

At the end of the 19th century, Portland had some 90,000 residents, a thriving immigrant population—many from China and other parts of Asia—and the busiest port on the West Coast north of San Francisco. It also had a reputation for filth. With the relentless rain during the winter months, thick mud clogged the streets, along with horse dung and human waste. But Portland was an exciting place to live—a rapidly expanding, culturally diverse, and treed city. When Portland hosted the World’s Fair in 1905, two years after James Beard was born, an estimated three million visitors came.

Against this backdrop, little Jimmie grew up, his father’s distance compensated for by his mother’s tendency to spoil him. He shared Mary Elizabeth’s love of fine food, as well as of theater, opera, and a cosmopolitan perspective. He had a flare for drama, a notable singing voice, and a big personality that tended to catch the attention of adults while it alienated him from children his own age.

Mary Elizabeth had high expectations for her son. She expected the world to recognize his talents and uniqueness. Her desire was for him to become an opera star or a great actor—to have constant exposure to fabulous people, and to lead an interesting life directly in the public eye.

A Graduate (Not) of Reed College

At the age of 16, in 1920, James Beard enrolled in Reed College—a Beard, James Andrew, accompanied by an asterix is listed on page 76 of a slim book with a gray cover, the Catalogue of Reed College, Number Thirty-Eight. He attended classes at Reed, commuting from his home on Salmon Street, in 1920 and 1921.

Different stories have circulated over the years about why and how James Beard (also known to his classmates as “Jim” and “Jimmie”) left Reed after one and a half years. According to his biographer, Robert Clark, he was expelled for being openly homosexual.

Beard delighted in wild-harvested chanterelle mushrooms, Oregon huckleberries, fresh-caught salmon, and many other foods found in his native land.

When an American Masters documentary about his life, “America’s First Foodie,” came out in April 2017, viewers were told the same. But no college spokesperson would verify that story for me. Over the years Reed, a liberal arts college that prides itself on having progressive values and being a welcoming place for quirky students, has chosen not to comment on the subject.

What we do know for certain is that from the moment he stepped onto Reed’s 116-acre campus of rolling hills and twisting paths just five miles from the center of Portland, Beard was something of a phenomenon. He is mentioned in almost every issue of the student-run school newspaper, the Reed College Quest, from September 1920 when he first matriculated to 1921 when he left. That much notice is especially unusual for a first-year student, Reed archivist, Maria Cunningham, tells me.

It’s one of those spectacular spring days in Portland—bright sun, clear blue sky punctuated by fluffy white clouds reminiscent of a Claude Monet painting—when I drive to Reed College, park on the West side, and walk to the Hauser Library. The main floor of the library is filled with long tables of picked-over free food, there to keep bleary-eyed students studying for finals fueled as they quest for knowledge.

As I descend two flights of stairs to the Reed archives, which are in the building’s basement, I can’t help thinking that James Beard would have frowned at the unidentifiable mush on display in large disposable aluminum trays—while he was not a snob about food, not really, and while he was quick to celebrate everything from home-style macaroni and cheese to the invention of the Cuisinart, Beard did have certain standards.

There are hundreds of interesting documents in the seven boxes of Beard archives that the college houses, including a letter Beard received a year before he died. This “remembering” letter, as its author, Esther K. Watson, describes it, is full of nostalgia. “My first memory of you was when my Father told us of your birth,” writes Watson in the letter, dated May 23, 1984. She goes on:

Our Mothers were very good friends so we shared in the good news of your arrival … I heard my Mother call your Mother so often that I still remember your phone number, East 1629 … I can vouch for the fact that your Mother was a wonderful cook. My most vivid memory is of her baking powder biscuits and those elegant teacakes which she taught me to make. They were basically rich baking powder biscuit dough to which she added raisins or currants. She cut the rolled dough in triangles and brushed the tops with cream. They were a toothsome delicacy especially enjoyed with some of your Mother’s perfectly blended tea.

After Beard was expelled from Reed, he left Portland for London for voice training lessons. It seems that Europe agreed with him, especially Paris and Berlin, where the attitude towards gay people was much more open than in America at that time. In Germany Beard fell in love with a handsome young man named Hans. But gallivanting around Europe at his mother’s expense was not financially viable for either of them, and Beard soon ended up back in the United States, making a home—and eventually a name—for himself in New York City.

Though he later described his expulsion from Reed as a “bitter, biting thing,” James Beard was not one to hold a grudge. Also in the archives are internal memos and letters back and forth from college officials to each other strategizing how best to woo Beard, as well as a copy of James Beard’s will. He graduated from college after all, at the age of 73, when Reed awarded him an honorary degree.

I could imagine his laughter when he explained the situation in a 1981 interview with Oregon Magazine: “They threw me out, and then later they called me back to get an honorary degree.

I thought it was so funny.” Though in 1982 he told a college representative who solicited him for a donation, “It would be nice to oblige you but this seems to be the year that everyone [has the] same horn to play and I have already spent my music,” he ended up willing the college the bulk of his estate.

A Foodie in New York City Teaching in Seaside

Unable to find gainful employment as an actor, but a notable cook and conversationalist among his friends, Beard finally began the career as a full-time food sensualist that he would become so famous for by opening an hors d’oeuvres catering business with a business partner named Bill Rhode in January 1939. He wrote his first cookbook in 1940 at the age of 37.

Based in New York City for his entire adult life, Beard taught cooking classes, hosted fabulous dinner parties, was a coveted guest, ate lavishly, wrote voluminously, and traveled extensively. He reveled in change. Even as he aged—and suffered from myriad health problems, including high blood pressure—he was known for his boundless energy, positive demeanor, and razor-sharp memory.

He returned often to the West Coast and in the early 1970s Beard started teaching cooking classes in the summer in the home economics department of Seaside High School, just south of Gearhart where he had spent his summers as a child. Newspaper articles about him from that time include his lavish praise for Oregon’s native foods. Beard delighted in wild-harvested chanterelle mushrooms, Oregon huckleberries, fresh-caught salmon, and many other foods found in his native land.

The sheer pleasure Beard takes in food and eating, though it caused him health problems later in life, is wonderfully contagious. In his 1944 Fowl and Game Cookery (later reprinted as Beard on Birds), he teaches readers how to enjoy eating everything from the familiar (chicken, turkey, duck) to the decidedly more exotic (squab, pigeon, snipe, woodcock, dove). He was exhaustive in his knowledge about food. In his 1954 James Beard’s Fish Cookery he offers recipes and advice about eating frogs, snails, and turtles, as well as for 80 different kinds of fish and shellfish. He also emphasized how fun eating can be. In his 1983 Beard on Pasta he recommends tiptoeing over plastic-wrapped udon noodle dough with your bare feet as the best way to knead it.

“There is always something to do,” Beard enthused to one reporter in 1980, when he was 77. “that’s the fun of it. Newness and change are the attractive parts of this life. I have the spirit I have because I like what I’m doing.”

Back to Gearhart

Mary Alionis, owner of Whistling Duck Farm in the Applegate Valley (between Medford and Grants Pass), is dropping off vegetables. She delivers mesclun salad mix and bunches of kale to the Ashland Food Co-op, boxes of bagged mixed greens to a fellow farmer at the Growers’ Market (now that Whistling Duck has their own on-site store, Alionis tells me, they don’t have a booth at the market anymore), and the first batch of ripe strawberries to a friend. Small, brilliant-red, and sun-ripened, the strawberries are so sweet they seem almost sinful.

Alionis’ face lights up when I ask her about James Beard. “He pioneered the farm to table movement,” she says. “He was all about fresh local foods at a time when food was becoming more industrialized. Now everyone agrees about the importance of good produce but back then… well, let’s just say he was a man before his time.”

A man before his time or perhaps a man who helped define his time, I find myself thinking as I sauté two big handfuls of Whistling Duck Asian greens—baby bok choy, komnatsuna, and hong vit radish greens—in some locally grown garlic.

James Beard died in New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center of heart failure on January 23, 1985. He was 81. His half-sister Lucille Bird Ruff, who led a quiet life married to a real estate salesman, is buried in a plot with an in-ground marker in Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland, where James Beard’s mother and father are also buried.

Unlike them, James Beard was cremated. His childhood friends, Mary Hamblet and Jerry Lamb, scattered his ashes on the Oregon Coast, at Tillamook Head and Gearhart Beach, returning his remains to the place he loved best and to the state that was always so proud of its provocative, exuberant, food-loving native son.

James Beard’s Books: His first cookbook was published in 1940; his last in 1983, just two years before his death. Throughout his life James Beard was tremendously prolific—writing not just full-length cookbooks and one memoir but also newspaper columns and magazine articles. Beard’s cookbooks offer readers hundreds of recipes delightful, quirky, and sometimes unexpected recipes that range from the utterly mundane (potato salad) to the wonderfully exotic (mud-roasted duck). They also offer a fascinating and idiosyncratic glimpse into America’s culinary culture. Here is a list of nearly all of James Beard’s books, along with the publisher and the date of publication:

Hors d’Oeuvre and Canapés (M. Barrows & Co., 1940)

Cook It Outdoors (M. Barrows & Co., 1941)

Fowl and Game Cookery (M. Barrows & Co., 1944. Retitled in 1989 as Beard on Birds)

The Fireside Cook Book: A Complete Guide to Fine Cooking for Beginner and Expert (Simon and Schuster, 1949)

Paris Cuisine (Little, Brown, 1952)

The Complete Book of Barbecue & Rotisserie Cooking (Maco Magazine Corp., 1954)

Complete Cookbook for Entertaining (Maco Magazine Corp., 1954)

How to Eat Better for Less Money (Simon and Schuster, 1954)

James Beard’s Fish Cookery (Little, Brown, 1954)

Casserole Cookbook (Maco Magazine Corp., 1955)

The Complete Book of Outdoor Cookery (Doubleday, 1955)

The James Beard Cookbook (Dell Publishing Co., 1959)

Treasury of Outdoor Cooking (Golden Press, 1960)

Delights & Prejudices: A Memoir with Recipes (Atheneum, 1964)

James Beard’s Menus for Entertaining (Delacorte Press, 1965)

How to Eat (and Drink) Your Way through a French (or Italian) Menu (Atheneum, 1971)

James Beard’s American Cookery (Little, Brown, 1972)

Beard on Bread (Knopf, 1973)

James Beard Cooks with Corning (1973)

Beard on Food (Knopf, 1974)

New Recipes for the Cuisinart Food Processor (1976)

James Beard’s Theory & Practice of Good Cooking (Knopf, 1977)

The New James Beard (Knopf, 1981)

Beard on Pasta (Knopf, 1983)

James Beard is also the subject of two lengthy biographies: Evan Jones’s Epicurean Delight: The Life and Times of James Beard (Knopf, 1990) and Robert Clark’s James Beard: A Biography (HarperCollins 1993), as well as the documentary film, “America’s First Foodie” (2017), directed by Beth Federici in collaboration with American Masters.

Jennifer Margulis, Ph.D., is an award-winning journalist, Fulbright grantee, and frequent contributor to the Jefferson Journal. She produces radio features for Jefferson Public Radio and is the author/editor of eight books. Her most recent,

The Addiction Spectrum, co-written with Paul Thomas, M.D., presents a unique, outside-the-box, holistic approach to solving the addiction crisis

in America. Learn more about her at www.JenniferMargulis.net.